What 19th Century Painters Can Teach Us About Thriving in the AI Age

A story about panic, epic beards, and how to reinvent yourself when technology changes everything

I bet you're thinking something like:

Hold up, Germán! A post about 19th century painters on an AI blog?

Absolutely! That's exactly what you're going to read here, and if you stick with me, you'll understand why (seriously, just trust me on this).

Now, let's dive in.

What happens when a machine starts doing something better than you? Something you took real pride in.

I've been wrestling with this question for years. I even have terrible jokes about it. I used to say that when forks were invented, someone definitely complained we'd lose the fine art of eating with our hands.

Recently, this question hit me again. People are asking a fair question: Are we giving away our creative power to AI?

There's real weight to that concern... though I'm not entirely convinced we should panic. Because I think we've been here before.

Something remarkably similar happened when painters first met photography. Imagine spending years mastering the art of capturing reality on canvas... and then a machine shows up that does it in minutes!

"From this day forward, painting is dead"

Meet Paul Delaroche. Paul was one of the most celebrated painters of the 19th century.

Paul, like every painter of his time, dedicated his life to creating realistic scenes with painstaking precision.

Paul painted breathtaking historical scenes and created portraits with mind-blowing detail and technique. His self-portrait speaks for itself, but check out this portrait of Henriette Sontag. Notice how every fabric fold, every strand of hair, every shadow is absolutely perfect. Paul was a champ.

Then one day, Paul discovers this revolutionary new technology called artificial intelligence photography, and his world gets flipped upside down. Legend has it (though we can't confirm this) that when Delaroche first saw what photography could accomplish, he declared:

From this day forward, painting is dead

– Paul Delaroche

Can you picture what was going through Paul's mind?

(Cue tragic 1840s scene)

Paul holds a photograph in his hands, studying the details (impossible to achieve even with years of practice). He thinks about all the time he spent mastering proportions, anatomy, perspective... trying to do what a machine can now create in minutes.Sound familiar?

I imagine Paul with this stunned look on his face, thinking something like:

"So... you don't need fifteen years of practice to paint well anymore?... what the hell am I supposed to do now?"

Paul had every right to be worried. Back then, a huge chunk of painters' income came from making portraits, so this technology was a direct threat to artists. Many lesser-known painters actually quit painting altogether and switched to photography.

After the initial shock, something interesting started happening. Artists realized that photography hadn't killed painting - in fact, several of them discovered that photos could actually help them a lot.

They used it, but not everyone admitted it

After the initial shock, something interesting started happening. Artists realized that photography hadn't killed painting - in fact, many of them discovered that photos could actually help them out big time.

Think about it: instead of making a model hold some crazy pose for hours (maybe standing on their head with a finger on their nose?), you could snap a photo and use it as reference. Or if you wanted to paint a landscape at exactly 5:43 PM in winter. A photo makes life easier, right?

The problem? Some of these painters conveniently "forgot" to mention that photography was one of their tools.

Not all of them, but plenty did - and here's why: back then, art was all about being a "genius." You know, that special person who could see what others couldn't and put that vision on canvas. And obviously, a true genius had to do everything by hand. Using machines? That was beneath them.

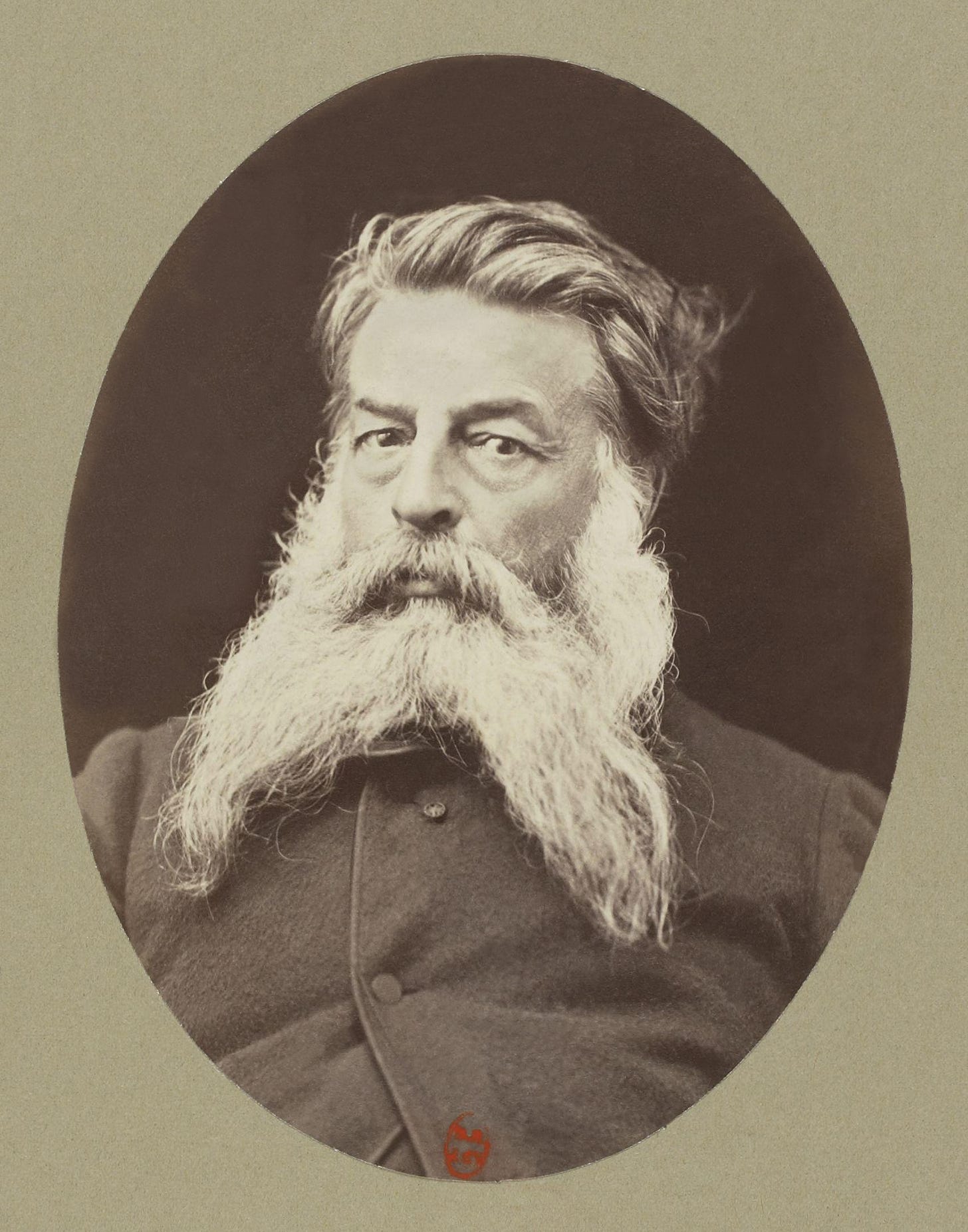

Take Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, for instance (definitely the owner of history's most epic beard). He admitted he consulted photos "the way Molière consulted his servants." That line says everything. He used them, but wouldn't give them any real credit.

What a magnificent beard! Can you imagine what a tragedy it would be if he'd shaved it off?

Actually, you don't have to imagine it - here you go ;)

No contest - that beard is legendary.

Sorry for the detour, but I had to address that. Moving on.

Not everyone hid their photography habit. Some painters took the completely opposite approach.

Take Eugène Delacroix, he was genuinely excited about this new technology and had zero shame about using it.

Well, "excited" might be putting it mildly... Delacroix actually thought photography had massive potential... if used with real talent. Here's what he wrote in his diary:

Let a man of genius make use [of photography] as it should be used, and he will raise himself to a height that we do not know.

– Eugène Delacroix

For Delacroix, the problem wasn't the tool - it was who was using it. He clearly didn't think anyone had figured out how to use it properly yet.

But other painters didn't get so wrapped up in philosophical debates about the "proper use" of photography...

Does it help me paint better? Then yes.

This is where painters started openly embracing photography as a legitimate tool. No more hiding - they used photos to study compositions, poses, movement. Whatever made them better painters.

Makes sense, right? The more mainstream a technology becomes, the less embarrassed we feel about using it (or at least admitting we use it).

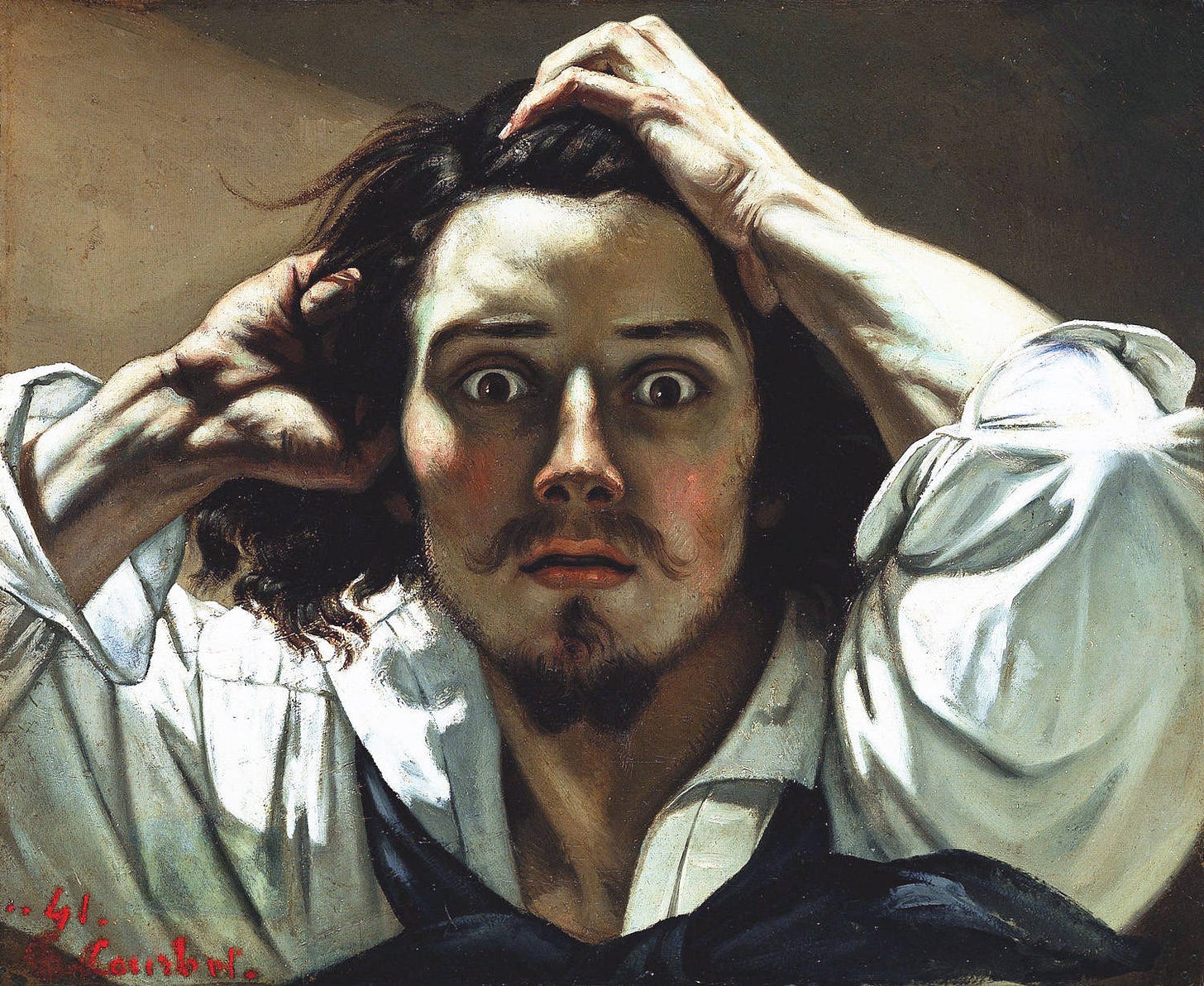

Take our friend Gustave Courbet and his self-portrait "The Desperate Man."

Courbet couldn't care less about justifying his use of photography in painting - he used it because it worked. End of story.

Gustave painted massive scenes packed with people and complex compositions. Picture trying to get seven people (and two dogs) to hold their poses for hours on end.

This painting, for instance, measures over ten feet wide by nearly seven feet tall. Definitely not an afternoon project.

Can you imagine those poor models trying to hold their positions? And don't get me started on keeping those dogs in the bottom right corner still (maybe that's why he looks so desperate in his self-portrait).

Wouldn't photos make way more sense? At least as a starting point to capture the scenes and people that would end up in the painting?

Absolutely. It was simpler, more practical, and Gustave was totally fine with that. If a camera helped him work better, he'd use it. And he wasn't shy about saying so either.

Now that photography was no longer the enemy, painters started asking themselves a different question: What if I start painting what the camera CAN'T do?

Painting what the camera can't see

Photography had become the ultimate way to capture reality. No argument there. So what happened to painting?

Suddenly it wasn't cool anymore to paint something a machine could do better... so something fascinating happened. Painters started asking themselves: What if I focus on what the camera can't capture?

Think about this for a moment. Artists began transforming art itself... in a way, photography's existence freed them to explore what lay beyond mere representation. This is the moment we can see art change forever.

It was no longer about copying reality - now artists started doing wild, experimental things. If cameras could capture reality, why not capture the feeling of a moment instead? That's how Impressionism was born.

Hold on - I'm getting sidetracked from the story, but I need to make a point.

When we talk about technology, we always focus on what it can do for us. But there's something we rarely notice: how it also forces us to expand our horizons and attempt things we never imagined before. It's like each new technology pushes us to reinvent ourselves.

Sure, photography wasn't the only thing that changed painting. New pigments played a role, trains that could take artists to the countryside, even Japanese woodblock prints. But I believe photography was the catalyst that accelerated everything.

Okay, back to the story.

Take a look at this, for example:

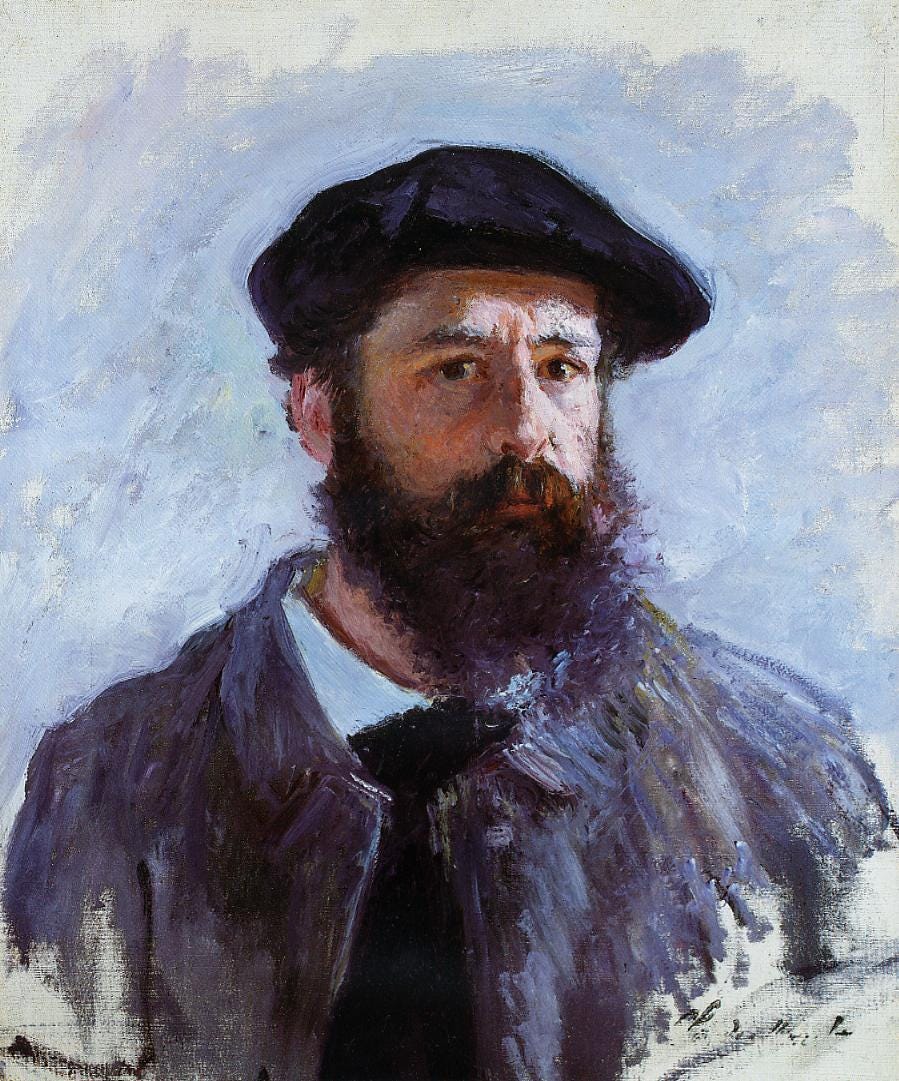

This couldn't be more different from a photograph! Here, our friend Claude Monet shows us how art can go way beyond just copying a scene.

Look at this painting. No sharp details, no crisp lines - it's pure feeling. Claude wasn't trying to document what the port of Le Havre looked like. He wanted us to experience what it felt like to be there, on that specific morning, in that exact moment (that would never come again).

My only merit is having painted directly from nature with the aim of conveying my impressions of the most fleeting effects.

– Claude Monet

Plenty of other artists took similar paths, each finding their own way to paint what cameras simply couldn't capture.

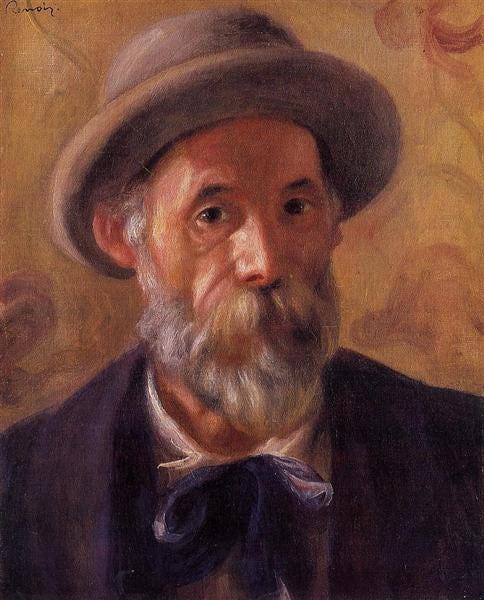

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, for instance, specialized in something no photograph could transmit: pure, unbridled joy.

Look at this scene. Pierre-Auguste wasn't documenting some event - he was capturing the sensation of being right there, soaking up the energy and happiness of people just enjoying life. Photos from 1876 typically showed serious faces and stiff poses, but this explosion of light, movement, and pure joy? Impossible!

Oil paint tubes, easily portable, allowed us to paint from nature. Without tubes... there would have been no Impressionism.

– Pierre-Auguste Renoir

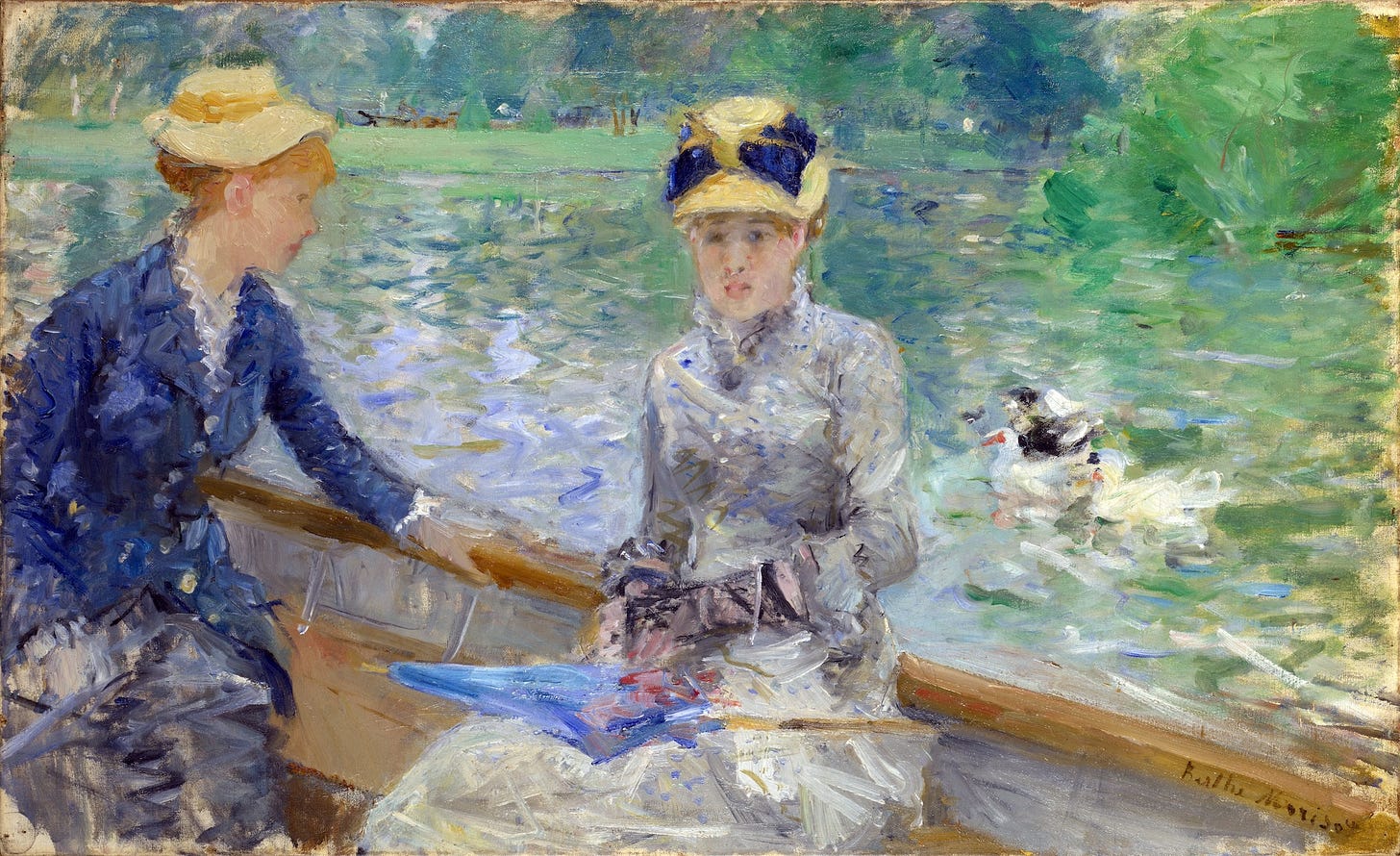

Berthe Morisot carved out her own territory by capturing those intimate, everyday moments that cameras couldn't really see. Her paintings of women and children, lazy summer days by the water - they had an emotional depth that was entirely her own.

Check out this scene. Berthe wasn't just painting two women in a boat - she was capturing that perfect summer feeling. Pure atmosphere and emotion, something no photograph could ever convey.

My ambition is limited to capturing something ephemeral.

– Berthe Morisot

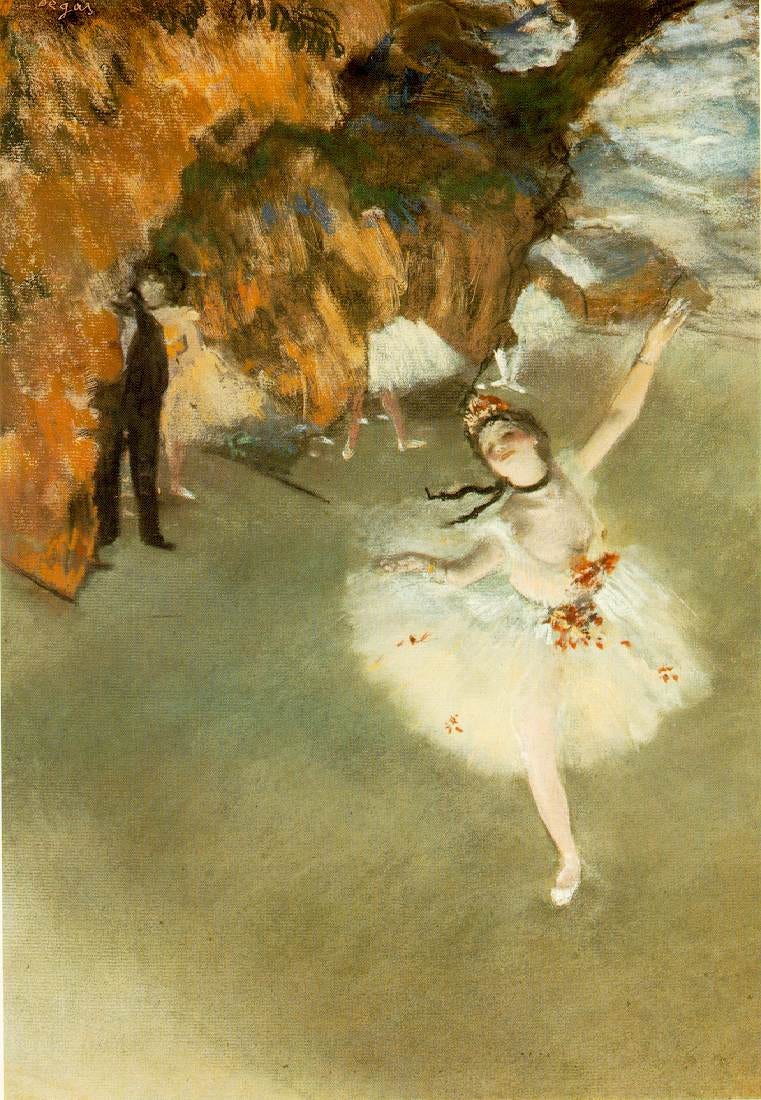

Edgar Degas took yet another route. He became fascinated with capturing movement and those intimate moments nobody else bothered to notice.

Edgar's dancers don't strike the graceful poses you'd expect in some fancy portrait. He painted the sweat, the exhaustion, the backstage reality. Weird angles, bodies caught mid-motion, the unglamorous truth behind the performance.

They call me the painter of dancers. They don't understand that the dancer has been for me a pretext to paint beautiful fabrics and represent movement.

– Edgar Degas

Here's the thing - this whole "paint what the camera can't see" approach didn't just stop in 1900. Let me jump ahead to the 20th century for a second.

20th Century

I know, I know... I promised to stick to 19th century painters, and here I am making an already long post even longer by dragging in the 1900s.

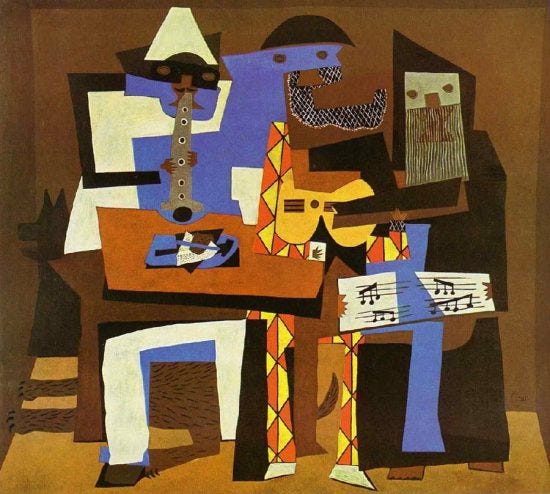

Just a quick detour to remind you that Impressionism wasn't the finale - it was the opening act. During the 20th century, painters completely shattered the rules. Case in point: this Pablo Picasso masterpiece!

Perfect excuse to showcase one of my all-time favorites, Three Musicians, hanging in MoMA in NYC.

Picasso isn't trying to show you what three musicians actually look like, he's deconstructing reality and rebuilding it from scratch. Geometric shapes, flat colors, impossible forms. And yeah, there's definitely a dog hiding under that table (in case you missed it).

No camera could ever pull this off... as Picasso put it:

I paint objects as I think them, not as I see them.

– Pablo Picasso

Nobody died in the end

Today nobody claims photography killed painting. Each medium found its niche. Sometimes they overlap, sometimes they don't. But both are alive and well.

Painting didn't vanish. It evolved. It stopped trying to compete and started exploring new territory. Photography found its groove. It went from being the supposed destroyer of everything to just another tool in the toolkit. And painting stayed painting - just without the burden of having to mirror reality perfectly.

Is the same thing happening to us with AI?

I think it is. We seem to be living through stages remarkably similar to what those 19th century painters experienced:

"This is going to wipe us out"

The Paul Delaroche moment.

This is where tons of people still find themselves. Copywriters watching ChatGPT churn out flawless social media posts in seconds. Designers seeing Midjourney generate stunning visuals in minutes. Programmers watching Claude write code faster than they can even think through the problem. It's that same existential dread: "If a machine can do my job, what do they need me for?"

Sound familiar? It's Paul's exact fear, except now we get bombarded daily with headlines like:

AI will put ________ out of work (insert whatever profession is trending)

This isn't happening overnight, but let's be real - technology moves roughly 3.7 million times faster now than it did in 1840. The knee-jerk reaction is to deny it, fight it, hunt for reasons why "this won't actually work" or "people will always want the human touch." (I'm sure you've heard all the arguments.)

"I use it, but nobody needs to know"

The "you use AI for that? How embarrassing!" era

Plenty of people are quietly using ChatGPT for tricky emails, Claude for brainstorming, or (ahem) to help with blog content creation. And don't get me started on AI in academics - from homework to exam answers.

All perfectly fine, but when someone asks how they pulled it off, they "mysteriously" forget to mention their AI sidekick. (Especially when we're talking about test-taking, right?)

This phase is loaded with contradictions. They know the tool helps, but they're terrified of judgment. What will people think? That I'm less creative? That I'm cheating? So they sneak around with it like some guilty secret.

"I use it and I'm thriving"

The Courbet approach: Does it help me work better? Then I'm using it. End of story.

This is exactly where I am right now. I use AI completely openly because it makes me more efficient, more creative, and lets me focus on what actually matters to me. I write this blog with help from Claude and ChatGPT, I use AI for images too, and I'm totally fine saying that.

It's like Gustave and his photographs (massive difference in scale aside), if a tool helps me do better work, I'm going to use it. No philosophical hand-wringing about "the soul of art" or "the purity of human creation." There's work to get done, and if AI helps me do it better, bring it on.

At this stage, you stop seeing AI as the competition and start viewing it as an incredibly powerful tool. Just like when painters stopped seeing photography as the enemy and started using it to create better art.

"It pushes us beyond"

The revolution that's coming.

This is when we stop trying to beat the machines and start doing what they can't (don't ask me what that'll be - I honestly have no idea).

The Impressionists didn't try to out-realism the photographs. They painted what photographs couldn't capture.

I can't even imagine what our version of "Impressionism" will look like in the AI age. I'm not some guru - I'm just as clueless as everyone else here. Maybe it'll be something deeply human, tied to emotions or lived experience. (Like the Impressionists did.) But beyond that? Your guess is as good as mine.

History repeats itself

It's as if each new technology arrives saying something like "Don't worry, I'll handle this boring/repetitive/mechanical part, you focus on what's really interesting”.

Photography took care of copying reality, and painters were able to focus on other things. Like conveying emotions or giving us their own perspective. They didn't lose their work, they made it more human.

With AI something similar is happening. It's taking charge of calculations, first drafts, repetitive tasks that used to take time away from what's important. We can focus on... well, we're still figuring out exactly what. But I think it'll be things that require lived experience, human perspective, emotional connections. Those things a machine can simulate but not really understand.

The question isn't whether AI is going to change our work. It already is. The question is whether we're going to resist like Paul Delaroche, or whether we're going to find our own "Impressionism."

What do you think is going to happen?

That's it! I think this is the longest post I've written, and I really appreciate you for making it all the way here. I'd love to know what you think :)

Since we talked about art, I wouldn't want to leave without sharing some of the family's works 😊:

See you in the next post!

G